Virginia Woolf to her sister

Virginia Woolf to her sister

A compilation of a series of love letters addressed by Jacques Derrida to an unnamed loved one.

From The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond

LETTERS

Between 1946 and 1975, Iris Murdoch corresponded with the French poet and novelist Raymond Queneau, a successful author sixteen years her senior. Published for the first time, the letters here are part of a collection recently acquired by the Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies at Kingston University, London.

It is likely that Murdoch destroyed all of Queneau’s letters to her.

14 July 1946

4 Eastbourne Road

Chiswick

London W4

Well now (your letter of 10 July) – I am truly very sorry to have been, even for a moment, a further problem & embarrassment for you. Thank you however for writing frankly. Please don’t think that I ‘expect’ anything of you – beyond, I hope, your continued friendship. We have expressed to each other our sincere ‘sympathie’ – that remains, I think? For the rest, our ways lie pretty far apart and I see no reason why our relationship should be a problem for either. Please, please don’t distress yourself about it. I well realize that your moral and emotional situation must be most unhappy – I sympathise very profoundly. I will not be a complicating factor. You know that I care about all this; I have become very attached to you & shall certainly remain so, but I don’t think there is any cause for agitation in that.

I am trying to work, but London is more nerve rending than ever. I have finished ‘Etre et le Néant’, thank God, with much admiration & some flutters of criticism. It stops just where I want to begin; I suppose I shall now have to do some thinking for myself. (Or shall I just wait till Sartre publishes his Ethics?) MacKinnon at Oxford seems to be going through some sort of spiritual crisis & can’t see me. A bunch of goddamn neurotics I have for friends. I have continued a little with Pierrot & find this the one soothing occupation in a somewhat ragged world.

Thank you very much for ‘Les Ziaux’, which I have not yet had time to read. Work well at Avignon & don’t worry yourself to death. I wish you most heartily the strength to solve your problems.

Now & always I remain your calm tender devoted reader & friend.

Iris

PS My surname ends with an H not a K. Pax tecum –

24 April 1947

4 Eastbourne Road

Chiswick

London W4

[…]

I was most glad to have your news, or rather lack of news, abstention from news. How bloody of Dial Press to have second thoughts now – still, I imagine it means only delay? I hope Lehmann hurries up with his project for our island. I feel most impatient to see you in English. I hope your play is going down well? But most of all I long for Gueule de Pierre III. (If the devil were bargaining with me for my soul, I think what could tempt me most would be the ability to write as well as you. Tho’ when I reflect, in my past encounters with that character he has not lacked other good bargaining points –).

For the rest – I am glad that you have reasons for being happier, even if you don’t yet fully profit by them. Confidences – yes, I know, I too would like to ‘talk’ – but perhaps I’d better not, for the moment anyway. Also there are some things which it is almost impossible to explain, to expose, however violently one wishes to. (Another language problem.) Spoken of they seem … melodrama, or an attempt to trip the other into complicity. Yet for all that I’d like to talk with you frankly one day (about my own histories, I mean). You are important to me in all sorts of ways. As a symbol, yes – one distant undiscovered magnetic pole of my own uncertain mind. But as yourself too – a voice in my life, and more, yourself, with your curious laugh and nervous ways. Perhaps I behaved foolishly in Paris (forgive me) but my affection for you was then and is now most most sincere and tender.

After much indecision about jobs, I’ve decided to apply for two next month – one a year-long studentship at Cambridge, & the other a lecturership in philosophy at Liverpool university. I don’t know what my chances are for either. The Cambridge thing is to be applied for by June 1st – rather late in the year, so that hanging on for that means letting go various jobs which I might chase after now. But I yearn for Cambridge. (Oxford is intolerable to me now – I can’t help tho’ wanting to ‘start again’ in another city which is exactly like Oxford but all different.) – This thing is competitive however, & I daresay I shan’t get it. So – Liverpool, or else Bradford Technical Institute – or God knows what yet more frightful hack task in some red brick town in some marsh in the midlands. On verra.

[…] I’d like to talk with you – this afternoon, say – enormously at leisure, sitting outside some café in the Boulevard something-or-other, with the sparrows hopping on the table, & the people passing. And discuss Universal History and Human Destiny and our history & our destiny, and politics and language – I need so much to talk & talk – but the chances so rarely come.

I hope that, truly, life goes better with you. I wish you very well. Pardon me if I say things amiss. I am deeply concerned that you should be happy & solve your problems. Write if you’ve time, but never mind if you haven’t. More news from me later. Fiat pax in virtute tua.

Devotedly, yours

I

21 Sep 1947

4 Eastbourne Road

Chiswick, W4

My dear, I am back in London, God help me. There is the usual collection of nerve rending letters waiting, inter alia, a ms of mine (a novel written in ’44) politely rejected by a publisher – & a request from a learned body that I should lecture on existentialism in London in the autumn. […] I feel alarm at this – sometimes I think my playing the philosopher is a great hoax & one day someone will denounce me. You see already I’m fretting about these trifles. But not all trifles – some distressing letters too from sad friends.

You said that love between a man & a woman made always some sort of basis for life. Yes. Yet how rarely it occurs without hurt to one or both parties – or rather both, for if one is hurt both are hurt. Yet I don’t know – I can’t tell for other people really, only for myself.

I meant all I said last night – but don’t be distressed – very simply & loyally. I hope & pray we won’t ever harm each other. I’m very tired at the moment – sort of drunk with tiredness & nothing to eat, you know the way one can be. My parents are out playing cards. It’s late. I can’t help wishing for simple things, simple solutions. I wish I could see you often & get to know you. Maybe I will get to know you better in time.

I’ll write again in a few days when I’m feeling less feverish. Thank you, for very many things. I’m happy that I know you and happy that I love you.

I’m so glad you like Prince Myshkin.

I hope all goes very well with all your projects.

Most tenderly

I am yours

I

24 August 1952

I’m sorry about the scene on the bridge – or rather, I’m sorry in the sense that I ought either to have said nothing or to have said something sooner. I was in extreme pain when I came to see you chez Gallimard on Friday – but what with English habitual reticence, and your cool way of keeping me at a distance I could say nothing altho’ I wanted desperately to take you in my arms.

On the other hand, if I had started to talk sooner I might have spent the rest of the time (such as it was) in tears, & that was to be avoided. I’m glad I said at least one word to you however. I can’t tell you what extravagance I have uttered in my heart & you have been spared. I write this now partly (for once) to relieve my feelings – and partly because you were (or affected to be?) surprised at what I said.

Listen – I love you in the most absolute sense possible. I would do anything for you, be anything you wished me, come to you at any time or place if you wished it even for a moment. I should like to state this categorically since the moment for repeating it may not recur soon. If I thought I stood the faintest chance, vis à vis de toi, I would fight and struggle savagely. As it is – there are not only the barriers between us of marriage, language, la Manche and doubtless others – there is also the fact that you don’t need me in the way in which I need you – which is proved by the amount of time you are prepared to devote to me while I am in Paris. As far as I am concerned this is, d’ailleurs, an old story – when you said to me once, recommençons un peu plus haut, it was already too late for me to do anything of the kind.

(I wrote thus far in a somewhat proletarian joint in the Rue du Four, when a drunken female put her arm round me et me demandait si j’ecrivais à maman. J’ai dit que non. Alors elle m’a demandé à qui? and I didn’t know how to reply.)

I don’t want to trouble you with this – or rather, not often! I know how painful it is to receive this sort of letter, how one says to oneself oh my God! And turns over the page. I can certainly live without you – it’s necessary, and what is necessary is possible, which is just as well. But what I write now expresses no momentary Parisian mood but simply where I stand. You know yourself what it is for one person to represent for another an absolute – and so you do for me. I don’t think about you all the time. But I know that there is nothing I wouldn’t give up for you if you wanted me. I’m glad to say this (remember it) in case you should ever feel in need of an absolute devotion. (Tho’ I know, again, from my own experience, how in a moment of need one is just as likely to rely on someone one met yesterday.)

Don’t be distressed. To say these things takes a weight from my heart. The tone dictated to me by your letters depuis des années me convient peu. I don’t know you quite well enough to know if this is voulu or not. Just as I wasn’t sure about your ‘surprise’ on the bridge.

To see you in this impersonal way in Paris, sitting in cafés & knowing you will be gone in an hour, is a supplice. But I well understand & am (I suppose) prepared to digest it, that there is no alternative. If I thought that you would be pleased to see me in Sienna I should come. But (especially after writing to you like this) there is very little possibility of my being able to discover whether you would be pleased or not.

[…]

It’s happened to me once, twice, perhaps three times in my life to feel an unconditional devotion to someone. The other recipients have gone on their way. You remain. There is no substitute for this sort of sentiment & no mistaking it when it occurs. If it does nothing else, it shows up the inferior imitations.

I wish I could give you something. If anything comes of this novel (or its successor), it’s all yours – as is everything else I have if you would. I love you, I love you absolutely and unconditionally – thank God for being able to say this with the whole heart.

I feel reluctant to close this letter because I know that I shan’t feel so frank later on. Not that my feelings will have altered, ça ne change pas, but I shall feel more acutely the futility at these sort of exclamations. At this moment I am, même malgré toi, in communication with you in a way which may not be repeated. If your letters to me could be slightly less impersonal I should be glad. Mais ça ne se choisit pas. I have become used to writing impersonally too, & this was a mistake. My dear. It happens to me so rarely to be able to write a letter so wholeheartedly – almost the last but one was a letter I wrote to you in 1946. I love you as much as then. More, because of the passage of time.

Forgive what in this letter is purely ‘tiresome’. Accept what you can. If there is anything here which can give you pleasure or could in any bad moment give you comfort I should be very happy. I love you so deeply that I can’t help feeling that it must ‘touch’ you somehow, even without your knowing it. Again, don’t be distressed. There is so much I should like to have said to you, & may one day. I don’t want to stop writing – I feel I’m leaving you again. My very very dear Queneau –

I

Frida Kahlo writes a personal letter to Georgia O’Keeffe after O’Keeffe’s nervous breakdown.

Peggy Phalan and Adrian Heathfield from “Blood Math”

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

vs.

Virginia Woolf in a letter to Margaret Davies dated March 27th, 1916

VIRGINIA WOOLF

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (1980-1992), C-print, 26.7 x 34.3 cm. (10.5 x 13.5 in, 1991

Letter to Carl George from Felix Gonzalez-Torres, May 12, 1988

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, installation view of solo show at the Andrea Rosen Gallery (curated by Julie Ault and Roni Horn), 2016

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For White Columns), C-print on jigsaw puzzle in plastic bag, 1990

Installation view of Floating a Boulder: Works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Jim Hodges at FLAG Arts, 2009-2010

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Love letter), C-print, 22.5 x 33.7 cm. (8.9 x 13.3 in, 1992

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Perfect Lovers), 1991

Felix Gonzalez Torres, “Untitled” (Love Letter From The War Front), 1988. Chromogenic print jigsaw puzzle in plastic bag, 7 3/8 × 9 3/8 × 1/16in. (18.7 × 23.8 × 0.2 cm). Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Paris Last Time) (1989), C-Print jigsaw puzzle, 7 ½ × 9 ½ in.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled" (Wawannaisa), 1991, C Print Jigsaw Puzzle In Plastic Bag, 7 ½ X 9 ½ In.

“In the early nineties, following the death of his lover from AIDS, and railing against the social inequalities and intolerance of the Reagan/Bush era, Felix Gonzalez-Torres wrote: ‘How is one supposed to keep any hope alive, the romantic impetus of wishing for a better place for as many people as possible, the desire for justice, the desire for meaning, and history?’ [1] It is a question that haunts his art, and which remains pressingly relevant as one encounters this major show, installed in all three of The MAC’s gallery spaces.

Famously, Gonzalez-Torres appropriated the aesthetics of minimalism, encoding both personal and radical political content within a restrained formal vocabulary. His ostensibly simple gestures are rich in universal meaning, and abound in metaphors for the diminuition of the body and its passage from life into death…It is an art of light, reflections and shadows, formed of mirrors, festooned strings of light bulbs, curtains of diaphanous gauze or plastic beads; and stacks of posters and so-called ‘spills’ of cellophane-wrapped sweets from which we are each invited to take one home.”

—Ian Massey

“In a way, this letting go of the work, this refusal to make a static form, a monolithic sculpture, in favour of a disappearing, changing, unstable, and fragile form was an attempt on my part to rehearse my fears of having Ross disappear day by day right in front of my eyes…Memory offers a path back to the other side of the line between life and death: it is all that remains after the disappearance of the body.”

—Feliz Gonzalez-Torres

The following text is from an interview between the artist and Ross Bleckner at Bomb:

“RB I think that the art writing, to put it mildly, is slightly out of touch. And I would say that’s generous.

FGT We’re strong enough to be generous. If you’re weak, pussy-footed, you cannot be generous. You have to be very constricted and constipated about everything you own. But if you’re generous it shows you’re strong.

RB Exactly. So are you in love now?

FGT I never stopped loving Ross. Just because he’s dead doesn’t mean I stopped loving him.

RB Well, life moves on, doesn’t it, Felix?

FGT Whatever that means.

RB It means that you get up today and you try to deal with the things that are on your mind.

FGT That’s not life, that’s routine.

RB No, it’s not.

FGT Oh, yes, it is.

RB A lot in life is about routine, and hopefully we can make our routines in life as pleasurable as we know how. Because we connect to our work in a way that’s satisfying and we have some nice relationships. After that, how much more can you ask?

FGT That’s why I make work, because I still have some hope. But I’m also very realistic, and I see that …

RB Your work has a lot to do with hope; it’s work made with eyes open. That to me is very important. Work made with eyes open.

FGT It’s about seeing, not just looking. Seeing what’s there.

RB Do you look to fall in love? Do you need that as a situation? Does it inspire your work?

FGT How can you be feeling if you’re not in love? You need that space, you need that lifting up, you need that traveling in your mind that love brings, transgressing the limits of your body and your imagination. Total transgression.

RB You feel like you had that with Ross?

FGT A few times over.

…

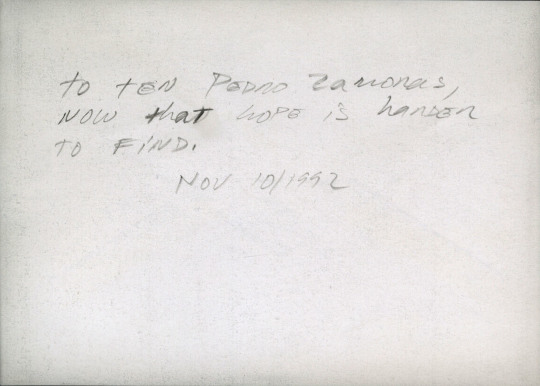

November 12, 1994. Photograph by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. (Reverse) © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

…RB Did [Ross] know he had HIV?

FGT No, the year before he got the diagnosis of AIDS he had his appendix removed and they tested the blood and it was HIV positive. But he was a fucking horse. He was 195 pounds, he could build you a house if you asked him to. It’s amazing, I know you’ve seen it the same way I’ve seen it, this beautiful, incredible body, this entity of perfection just physically, thoroughly disappear right in front of your eyes.

RB Do you mean disappear or dissipate?

FGT Just disappear like a dried flower. The wonderful thing about life and love, is that sometimes the way things turn out is so unexpected. I would say that when he was becoming less of a person I was loving him more. Every lesion he got I loved him more. Until the last second. I told him, “I want to be there until your last breath,” and I was there to his last breath. One time he asked me for the pills to commit suicide. I couldn’t give him the pills. I just said, “Honey, you have fought hard enough, you can go now. You can leave. Die.” We were at home. We had a house in Toronto that we called Pee-Wee Herman’s Playhouse Part 2 because it was so full with eclectic, campy, kitsch taste. His idols were not only George Nelson and Joseph D’Urso, but also Liberace.

RB That’s a very nice combination.

FGT Love gives you the space and the place to do other work. Once that space is filled, once that space was covered by Ross, that feeling of home, then I could see, then I could hear. One of the beauties of theory is when you can actually make it into a practice.

…

RB So Felix, I’m curious to what degree the involvement with your work and with gay life, having a lover who’s died—I know that’s effected your work tremendously in the billboards.

FGT It’s also about inclusion, about being inclusive. Because everyone can relate to it. It doesn’t have to be someone who is HIV positive. I do have a problem, Ross, with direct representation, of what’s expected from us.

RB Why?

FGT What I’m trying to say is that we cannot give the powers that be what they want, what they are expecting from us. Some homophobic senator is going to have a very hard time trying to explain to his constituency that my work is homoerotic or pornographic, but if I were to do a performance with HIV blood—that’s what he wants, that’s what the rags expect because they can sensationalize that, and that’s what’s disappointing. Some of the work I make is more effective because it’s more dangerous. We both make work that looks like something else but it’s not that. We’re infiltrating that look. And that’s the problem I have with the sensational, literal pieces. I’m Brechtian about the way I deal with the work. I want some distance. We need our own space to think and digest what we see. And we also have to trust the viewer and trust the power of the object. And the power is in simple things. I like the kind of clarity that that brings to thought. It keeps thought from being opaque.

RB And deluded.

FGT I was visiting in Miami where I saw this beautiful video about someone dying. There was an image of someone swimming underwater and the sound was this very heavy-duty breathing, like someone couldn’t breathe, actually. And that for me would have been more than enough. But then of course they will not trust the strength of that imagery, the combination of imagery and sound. They had to add text to it and flack it up.”

Photograph of Felix Gonzalez-Torres (left), Ross Laycock (center), and Tommie Venable (right) in Paris, 1985.

Emily Dickinson, from one of her Master letters

Anne Carson from The Beauty of the Husband

— Rainer Maria Rilke, excerpt from “Letter XI,” Letters to Merline transl. by Jesse Browner (Paragon House, 1989)